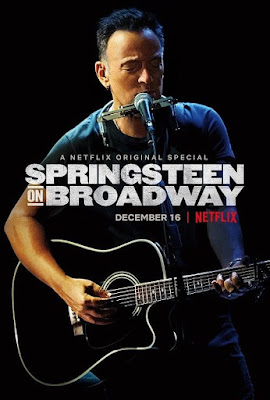

Inheriting the Flames: Springsteen on Broadway

Now that Bruce Springsteen's one-man show on Broadway is over, and the Netflix video is out and sporting a 95% rating on rotten tomatoes, with comments such as "transformative" and "a master class" coming from reviewers in the major New York papers, I'm re-evaluating my own thoughts on the show. Where and how did it resonate? And, why?

The show was based, in large part, on Springsteen's autobiography. I wasn't able to get beyond about page 80 reading the book, but then I got the audio book, read by Springsteen himself. There, the narrative seemed to take off, and I listened to the whole thing multiple times. Many of the items from the book that I found the most engaging, ween't in the Broadway show: sister Pam's hair getting caught in a blender, and Bruce still laughing about it, 50 years later! Or, the details of getting kicked out of his parents' former home after just one month of being on his own, and laughing about those, too. Or, most resonant to me, of having to dig through the seat cushions of the Pontiac to find enough pennies to pay the toll at the Lincoln Tunnel: for me, more than a decade later, it was exit 14 of The New Jersey Turnpike, the fare at the time was 70 cents, and I had a grand total of 71 cents in the vehicle -- the last 6 were pennies. And yes, I got the "no pennies" lecture, too.

Listening now to the show, I find that I'm drawn back to some of the first things that drew me to Springsteen more than 40 years ago: the struggle to find meaning, the "proof of life," and, more to the point of this show, the ongoing battles at home and within. As my friend Lauren Onkey noted in her summary for NPR, "Springsteen doesn't write about the insides of factories. He writes about the insides of our messy psyches and hearts."

Heck, I could write just about the shared memories that Lauren and I have from various Springsteen shows (if she'll let me, anyway): we met by being seated next to each other at a New Jersey show in July, 1999. Later that same year we drove from Minneapolis to Fargo to see a show - I lived in Michigan and Lauren in Indiana, at the time - after which she exited my vehicle, which I was driving at the time, in the parking lot in order to (successfully) intercept Bruce personally. That trip initiated a catch phrase that we still use today: "What was I thinking?" Or, the time on the floor at Asbury Park's Convention Hall, when Bruce Hornsby came out and they played "You Sexy Thing," and our gaping goofy grins at the "I don't believe this is happening" spectacle. Or being at the taping of Bruce Springsteen: VH1 Storytellers in Red Bank and circling around to the guitars after the show. Lauren left before a few of us encountered Bruce later that same evening at a local restaurant. What was she thinking? All of these events, and more, with Lauren and many other riders, speak a bit to our messy psyches, that we felt compelled to go to such ridiculous lengths to try to catch some of Bruce's magic trick. "What was I thinking?" is a reference not to the crazy things we did to be at some show, but rather the ones that we didn't do, the ones we could have gone to but where sanity intervened.

Bruce had a difficult relationship with his father. As did I, with my own father. That's not why I first started listening to Bruce back in 1977; Bruce really didn't start addressing that topic on record until Darkness on the Edge of Town came out the next year.

The first show I saw live, was in 1981. That night, Bruce introduced "Independence Day" as follows: "I remember when I was growing up, for all the 18 years that I was home, I never, I never once asked him what he was thinking about, and later I realized that what he was doing every night was he was sitting there dreaming... but what happened to him was he lost, he didn't have the strength any more or the way or the power to begin to make any of the things that he was dreaming about, but that's what the world does to you, I guess, I saw it take it out of him and now I go back and sometimes I see some of my old friends and I remember people that were, like, you know, when we were, like, 18 or 19, that were, that were real strong and real good inside that... that lost it somewhere along the way... and that's the hardest thing you gotta hold on to, I guess... so don't lose it." That seemed to describe us, too. That night's version of the song ended up being included on Live: 1975-85 -- without the story. That omission upset my brother, who was there with me that night. If you wanted that story, you had to have been there.

Like Bruce's dad, my father wasn't much in to saying "I Love You." The closest he came was a 10-second bit of counsel during our wedding party. It was good enough. It had to be.

The tangible similarities of what Bruce describes, to my own experience, are weak: My dad wasn't a drunk. He wasn't bipolar. He didn't typically wallow in the wasteland of "what might have been." He didn't pull up stakes and wave bye-bye to the great state of New Jersey. The resonances are elsewhere.

Bruce recorded "Adam Raised a Cain," and maybe I inherited the flames, no matter if Dad ever looked for someone to blame. As did so many of my friends who have hitched a ride on this train over the decades.

That's where I re-enter "Springsteen on Broadway." It's not that Bruce hasn't said this all before, in some fashion. In a sense, much of this show was summarized in that introduction to "Independence Day," more than 37 years ago. But by focusing this show entirely on the inside of his messy psyche and heart, Bruce helps open us up to our own.

Bruce has moved on, at least a bit, from the anger of "Adam Raised a Cain" and the departure of "Independence Day." It's more spiritual now: the show song for his father is "My Father's House." In it, he says, "my father was my hero, and my greatest foe." I still can't go that far, even now with my own father a decade gone.

During the show, when Bruce introduces "Long Time Comin'," he summarizes a conversation he had with his father shortly before his first child was born: "We are ghosts or we are ancestors in our children's lives. We either lay our mistakes, our burdens upon them, and we haunt them, or we assist them in laying those old burdens down, and we free them from the chain of our own flawed behavior, and as ancestors we walk alongside of them and we assist them in finding their own way, and some transcendence. My father, on that day, was petitioning me for an ancestral role in my life, after being a ghost for a long, long time."

I can't relate to the father driving 500 miles to have a conversation over morning beers, that style's not in my family. But this twist on ancestors and ghosts, summed up in a relatively short song that every hard core fan knows -- even though it sat unreleased for years and then came out only as an album track on the relatively poorly received 2005 album Devils & Dust -- that's what this show was about, to me. It's not necessarily the best song performances ever (for what it's worth, I dislike this version of "Born to Run," in which I can feel Bruce aging decades between the first verse and the last), so if it's live Springsteen you want, there are other better places for it out on http://live.brucespringsteen.net. It's a package deal: Come for the story, stay for the songs.

As for me: I'm about the same age now, that Bruce's father was on that evening in 1981. My ride continues.

The show was based, in large part, on Springsteen's autobiography. I wasn't able to get beyond about page 80 reading the book, but then I got the audio book, read by Springsteen himself. There, the narrative seemed to take off, and I listened to the whole thing multiple times. Many of the items from the book that I found the most engaging, ween't in the Broadway show: sister Pam's hair getting caught in a blender, and Bruce still laughing about it, 50 years later! Or, the details of getting kicked out of his parents' former home after just one month of being on his own, and laughing about those, too. Or, most resonant to me, of having to dig through the seat cushions of the Pontiac to find enough pennies to pay the toll at the Lincoln Tunnel: for me, more than a decade later, it was exit 14 of The New Jersey Turnpike, the fare at the time was 70 cents, and I had a grand total of 71 cents in the vehicle -- the last 6 were pennies. And yes, I got the "no pennies" lecture, too.

Listening now to the show, I find that I'm drawn back to some of the first things that drew me to Springsteen more than 40 years ago: the struggle to find meaning, the "proof of life," and, more to the point of this show, the ongoing battles at home and within. As my friend Lauren Onkey noted in her summary for NPR, "Springsteen doesn't write about the insides of factories. He writes about the insides of our messy psyches and hearts."

|

| some of Bruce's guitars, 2012 |

Bruce had a difficult relationship with his father. As did I, with my own father. That's not why I first started listening to Bruce back in 1977; Bruce really didn't start addressing that topic on record until Darkness on the Edge of Town came out the next year.

The first show I saw live, was in 1981. That night, Bruce introduced "Independence Day" as follows: "I remember when I was growing up, for all the 18 years that I was home, I never, I never once asked him what he was thinking about, and later I realized that what he was doing every night was he was sitting there dreaming... but what happened to him was he lost, he didn't have the strength any more or the way or the power to begin to make any of the things that he was dreaming about, but that's what the world does to you, I guess, I saw it take it out of him and now I go back and sometimes I see some of my old friends and I remember people that were, like, you know, when we were, like, 18 or 19, that were, that were real strong and real good inside that... that lost it somewhere along the way... and that's the hardest thing you gotta hold on to, I guess... so don't lose it." That seemed to describe us, too. That night's version of the song ended up being included on Live: 1975-85 -- without the story. That omission upset my brother, who was there with me that night. If you wanted that story, you had to have been there.

Like Bruce's dad, my father wasn't much in to saying "I Love You." The closest he came was a 10-second bit of counsel during our wedding party. It was good enough. It had to be.

The tangible similarities of what Bruce describes, to my own experience, are weak: My dad wasn't a drunk. He wasn't bipolar. He didn't typically wallow in the wasteland of "what might have been." He didn't pull up stakes and wave bye-bye to the great state of New Jersey. The resonances are elsewhere.

|

| The Walter Kerr Theater, November 17, 2017. |

That's where I re-enter "Springsteen on Broadway." It's not that Bruce hasn't said this all before, in some fashion. In a sense, much of this show was summarized in that introduction to "Independence Day," more than 37 years ago. But by focusing this show entirely on the inside of his messy psyche and heart, Bruce helps open us up to our own.

Bruce has moved on, at least a bit, from the anger of "Adam Raised a Cain" and the departure of "Independence Day." It's more spiritual now: the show song for his father is "My Father's House." In it, he says, "my father was my hero, and my greatest foe." I still can't go that far, even now with my own father a decade gone.

During the show, when Bruce introduces "Long Time Comin'," he summarizes a conversation he had with his father shortly before his first child was born: "We are ghosts or we are ancestors in our children's lives. We either lay our mistakes, our burdens upon them, and we haunt them, or we assist them in laying those old burdens down, and we free them from the chain of our own flawed behavior, and as ancestors we walk alongside of them and we assist them in finding their own way, and some transcendence. My father, on that day, was petitioning me for an ancestral role in my life, after being a ghost for a long, long time."

I can't relate to the father driving 500 miles to have a conversation over morning beers, that style's not in my family. But this twist on ancestors and ghosts, summed up in a relatively short song that every hard core fan knows -- even though it sat unreleased for years and then came out only as an album track on the relatively poorly received 2005 album Devils & Dust -- that's what this show was about, to me. It's not necessarily the best song performances ever (for what it's worth, I dislike this version of "Born to Run," in which I can feel Bruce aging decades between the first verse and the last), so if it's live Springsteen you want, there are other better places for it out on http://live.brucespringsteen.net. It's a package deal: Come for the story, stay for the songs.

As for me: I'm about the same age now, that Bruce's father was on that evening in 1981. My ride continues.

Comments